A recent report from the Ukraine war reminded me that I’ve been wanting to write about uniforms. The story is that a Russian tank crew drove their tank into a Ukrainian position and a Russian crew member asked if this was a good place to park the tank. The Ukrainians happily replied that it was a perfect place, but the Russians would now have to get out of the tank as prisoners.

This kind of confusion probably happens more often than we hear about since modern armies generally wear a variety of camouflage pattern uniforms and then cover them up with armored vests and body armor, again camouflaged. Ukrainian and Russian forces also share a common legacy of Soviet era equipment, offering further opportunities for confusion and mis-identification.

Ancient armies didn’t have uniforms in the modern sense, though they often were told by whoever was in charge what to wear and what weapons, headwear, and armor to use. Armies across history have often gone to war wearing an armband, sash, or hat band or trim in a specified color in order to distinguish one side from the other. This in part arose because armies were often composed of what were essentially independent contractors or sub-contractors who recruited fighters for their company and in turn negotiated terms of service and payment with the army leadership. To put such an army entirely into a single uniform style would have cost extra.

As modern nation states emerged in the 16th and 17th centuries, the Monarchs or governments doing the hiring of troops began to provide uniforms or at least specify how the soldiers should be dressed. This was encouraged by the difficulty of distinguishing one army from another on the smoke-filled battlefields dominated by early gunpowder muskets and cannon. Big, bold blocks of color appeared to work best, so the British army donned red coats. Peter the Great clothed his modern Russian army in green. The French toyed off and on with white (so hard to keep clean and, oh those bloodstains!) but finally settled on blue.

The following plates show the transition of American ‘uniforms’ during the Revolutionary war from militia dress to the uniforms of the Continental and State Line regiments of Washington’s Continental Army. (Uniforms of the American Revolution, John Mollo and Malcolm McGregor, Blandford Colour Series)

This selection of colors could sometimes lead to confusion. Washington dressed the Continental Army in blue uniforms, setting the standard for American soldiers for generations. But with the nation depending for almost a century on militia raised by the states, a wide range of uniform styles were seen in blue as well as other colors but in particular grey. During the War of 1812 with Britain, the British became accustomed to seeing grey clad American militia opposing them, often ineffectively. At the Battle of the Chippewa, 15 July 1814, General Winfield Scott led his newly raised regiments of regular US Army troops against the British wearing their new uniforms of grey cloth – because there wasn’t enough blue cloth. Seeing them arrayed in grey, British General Phineas Raill presumed that he was being confronted by American militia – until he watched them maneuver on the battlefield showing the precision drilled into them by Winfield Scott. Raill allegedly uttered the words still prized in the history of American arms to this day, “By God, those are Regulars!” A story possibly perpetuated by Winfield Scott claims that the grey uniforms worn to this day by cadets of the US Military Academy were inspired by this episode (rather than the fact that the uniforms wear well and were cheaper than blue ones).

Other distinctions were often introduced for practical reasons, like the tall headgear introduced for grenadiers and fusiliers so that their throwing of grenades or the shouldering of their brand-new flintlock muskets wouldn’t knock off their headwear. Most armies of the period chose the largest men to be grenadiers because of the weight of a bag of grenades and the fact that this job put them in the front rank of an attack on a trench or fortified place. The job would be revived during the First World War, especially among the German Strosstruppen who slung their rifles and carried bags of grenades with which to clear a path for their comrades. (Bundesarchiv image)

Additional new uniform ideas came from the practice of recruiting troops from ‘minority’ populations by authorizing them to wear uniforms that reflected their culture. In Britain, the Crown had outlawed the wearing of the kilt of the Scottish highlanders and their bagpipes were banned as “weapons of war” after the Rising of 1745. But the Crown did make an exception when it recruited a number of independent Highland companies to garrison outposts across the Highlands. When war with France came again and men were needed to fight the new conflict, these Highland companies were brought together and sent away to the wars as a new regiment already known as “The Black Watch”. At first the army thought to use these troops as light infantry based upon their abilities to move across the rough terrain of the Scottish highlands, but their performance on battlefields like Ticonderoga led to their increasing use as assault troops.

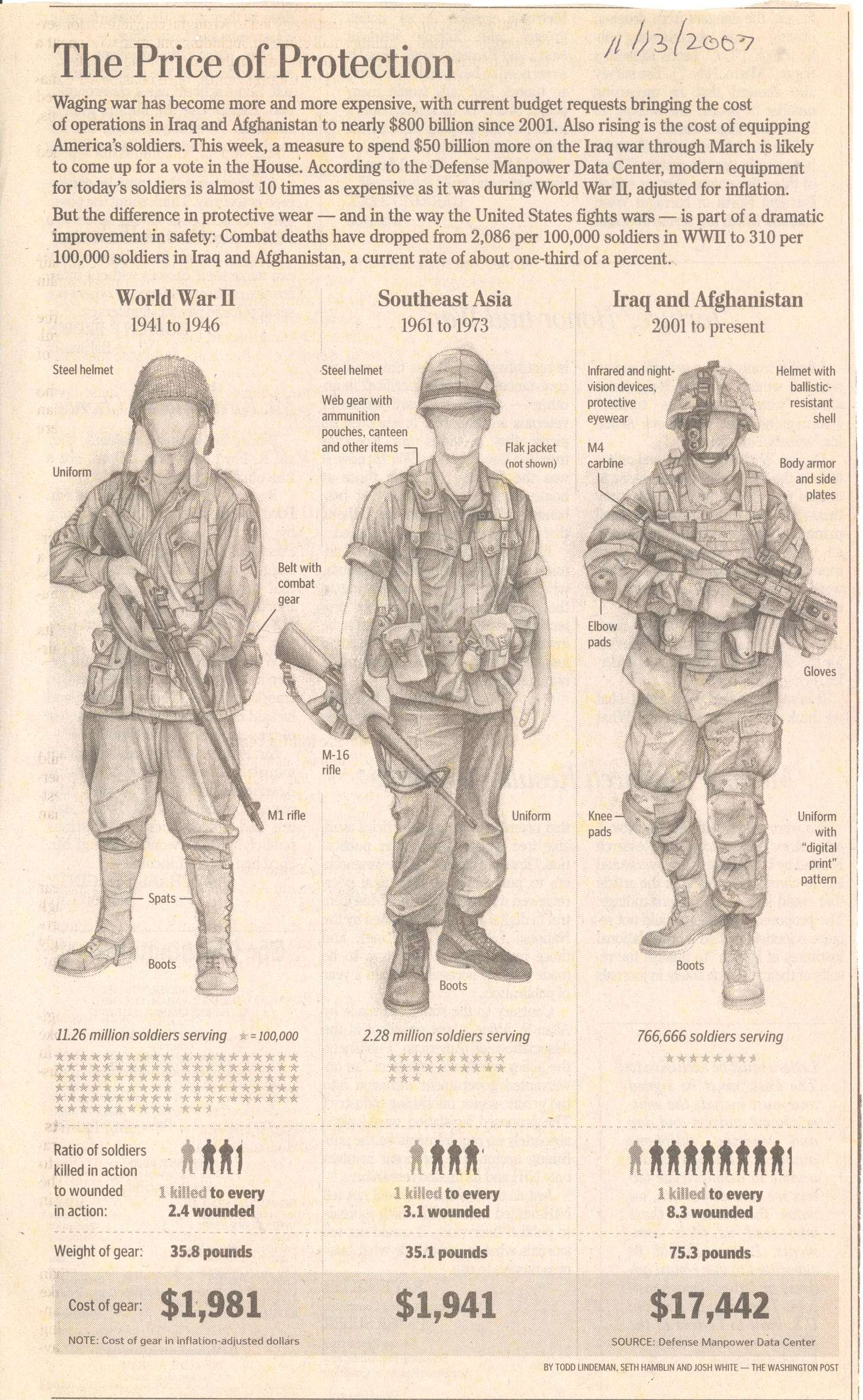

Today’s field service uniforms emphasize utility over fashion, a trend going back to the late 1800s in armies around the world. By the end of the First World War, every army had transitioned to dull shades of brown or green or grey to enable their soldiers to blend into the battlefield terrain. While there might be economies of scale due to putting everyone into the same basic uniform to start with, there is a lot of equipment added on. In 2007, the Washington Post featured a side bar to a story on the war in Afghanistan that illustrated the cost of fielding a World War II GI, a Vietnam era GI, and a soldier in the then ongoing operations in Afghanistan.

Of course, 2007 is now more getting close to 20 years behind us and battlefield wear and equipment continues to evolve and change as it adapts to different foes, different geography, novel weapons and technology. Having begun my career working alongside an army that had rank badges and other insignia on collars and shoulders, I had to adapt to an army in armored vests that moved rank to the center of their chests and other patches elswhere (using velcro, thanks NASA!). But modern unifroms continue to reflect a battlefield truism that now almost 125 years old - if you can see it you can kill it, so battlefield uniforms will continue to strive to conceal. We have come a long way from uniforms like those of Napoleon’s army, whose Polish Lancers wore a uniform that might appear to modern eyes to contradict their reputation for being among the French Emperor’s toughest soldiers. (Uniforms of the Napoleonic Wars in Color, 1796-1814, Devised and illustrated by Jack Cassin-Scott)

Excellent write up. In the indian subcontinent it is intresting to see the difference in the uniforms of the Mughals and the Armies of the Chhatrapti Shivaji. while the later were light and frugal on armoury the former were heavy and cumbersome leading to many lost opportunities and set back. One prominent example is : when Ikhlas Khan the Mughal commander under Daud Khan in the Battle of Vani-DIndori, (1670) left his troops who were busy tying up their armour and charged with a small party against Shivaji 's forces waiting across a pass (Kanchan-Manchan) with disastrous consequences. The Mughals lost that battle. Uniforms thus in the indian context have had operational consequences. Thanks loved reading your piece.

Still amuses me that when the French Army *eventually* accepted that red trousers were a bit conspicuous in the trenches ("Le pantalon rouge, c'est la France" notwithstanding), they conceded and switched to... horizon blue.