Dirt and Its Military Uses

"Dig in here, men"

For centuries warriors and soldiers went into battle standing together shoulder to shoulder or in looser formations, whichever arrangement worked for their spears, slings, swords, bows, axes, matchlock musket, flintlock, or rifled musket. But gradual and uneven change began with the introduction of gunpowder. As accuracy, range, and rate of fire increased, soldiers began to look for natural cover that offered concealment, or protection, or they would rearrange their environment to provide that protection. Among these efforts were trenches, fighting holes, foxholes, and variations.

The Romans left ample evidence of their abilities with spades and other tools of military engineering at Masada, Alesia, the defensive walls in England and on the Continent, the numerous remains of their legionary encampments, and their writings on how these were built. These inspired modern military engineers including the greatest, Marshal Vauban, of France.

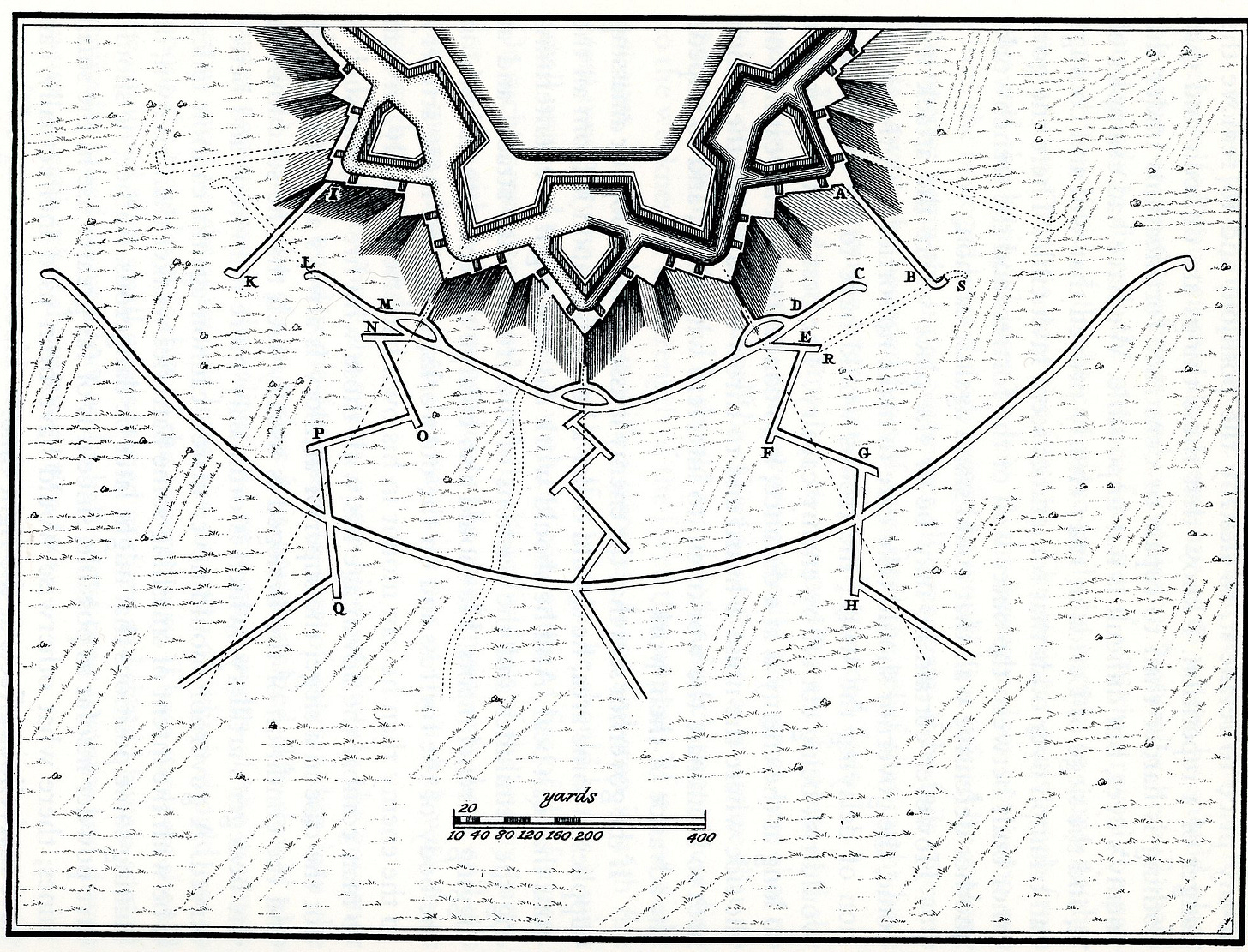

Vauban systemized the use of trenches and trenchlines in his instructions for the conducting of sieges. These trenches were dug parallel to the walls of the fortification to be besieged and ideally completely encircled the defenses. Even before the first ‘parallel’ of trenches was completed, zig-zag trenches would be started towards the defender’s positions. At a predetermined distance closer to the enemy, a new parallel trench would be begun from each of these narrower zigzag trenches which would themselves be widened to allow the movement of troops, cannons, and other equipment up to the new parallel. The purpose of these trenches was to bring cannon continually closer to the defender’s walls so that their bombardment would damage, breach, or destroy them. The defender might dig his own trenches out from his fortification in order to bring his troops close enough to attack the besieger’s trenches and possibly destroy or damage cannons and the besieger’s entrenching tools. Vauban also wrote about how to resist a siege. These techniques informed both the Allies and the Central Powers in the digging of the trenchlines in Flanders, France, Italy, and along stretches of the Eastern Front, thus the numerous references to the siege warfare of the First World War.

While tons of dirt were moved by the armies that fought the American Revolution, the War of 1812, the Napoleonic Wars, the Mexican-American War, it was mostly piled up in the form of redoubts and other above ground earthworks to support artillery while any trenches or ‘rifle-pits’ were ancillary to the defense works. The Crimean War and the American Civil War saw extended lines of trenches appear as defensive positions for the armies particularly at Sebastopol, Vicksburg, Petersburg, and Richmond.

The 1905 Russo-Japanese War saw extensive trenchworks as well as the introduction of barbed wire, machine-guns, and modern heavy cannon. Most outside powers sent observers to see this war for themselves, but leading military figures in just about every other nation concluded that these and other lessons were not relevant to their situation. European military leaders remained convinced that the next European war would be a short, swift campaign of movement and maneuver. When war struck in 1914, the armies were equipped with modern bolt-action magazine fed rifles, supported by machine guns and mobile quick firing cannon, but they still moved basically at the pace of the marching soldier.

American Civil War soldiers learned to begin preparing a fighting position whenever they stopped, usually by piling up rocks, fallen limbs, or just dirt. After the Civil War, soldiers fighting on the frontier often resorted to scooping out a hollow in the ground the size of their body in order to reduce their exposure to hostile fire. Such efforts would be overshadowed by the extensive trench works of the First World War only to return to common use in the Second World War. Through the years leading up to the First World War, most armies issued their soldiers an individual personal digging tool of some sort, but these were mainly for excavation of personal, individual holes. Any larger extended excavations of fighting positions often meant calling on the engineers and pioneer troops or even mechanical diggers (the Cold War Red Army had impressive stocks of these). During the First World War, the need for constant effort at restoring and repairing existing trenches as well as preparing new trench works was so great that the Allies recruited 140,000 Chinese workers alongside 25,000 Black South Africans in various in areas generally behind the front lines.

An important determinant about whether to dig foxholes or fighting holes versus trenches is how long you’re expected to be there. Fighting holes and foxholes were generally intended only for short term use. A second key factor is how many men you are putting in these positions and how many attackers they may have to face. By the time of the Second World War, you wanted at least two men in a foxhole so one could rest while the other watched for the enemy. Sometimes troops ended up occupying foxholes for days and possibly weeks. Extensive earthworks are a force multiplier for the defender, up to a point. But the longer you are planning to keep soldiers in foxholes or trenches the more you need to think about amenities for them. Troops really did not want to foul their foxholes and preferred to use nearby latrines if available or just a quick ‘cathole’ if necessary and the enemy allowed.

Slit trenches can be fought in multiple directions but trenchlines are mainly for combat in one direction with their zigzag support directions running back in the other direction to allow for movement of replacements, reinforcements, supplies, etc. Trenchlines are also usually intended for extended occupation. Extended occupation means that they need to incorporate sheltered areas for troops not actually on watch in the trench to rest and recuperate, and they need sanitation facilities. The horrors of the western front accumulated as the conflict was fought for such an extended period of time in roughly the same place, back and forth over the same ground. The excavation of new trenches and the restoration and repair of old trenches as the lines moved back and forth often found those doing the digging uncovering old burial sites, old medical treatment sites, and old latrines. In addition, the often heavy and prolonged artillery barrages could do the same thing.

Civil War trenches saw the addition of ‘headlogs,’ timbers placed horizontally along the trench edge towards the enemy leaving an opening below it as a viewport or gunport. This was a response to the appearance on those battlefields of sharpshooters and snipers. The 1905 Russo-Japanese war featured barbed wire entanglements in front of the trenches and machine guns in them.

As the trenches extended along the Western Front of the First World War, they became long term residences as well places of combat. These trenchlines also zigged and zagged at irregular intervals to prevent enemy troops entered the trenches from just firing down a long straight trench line. Now they had to expect a defender just around that bend. Before long they often incorporated large underground chambers to be used as barracks and storage spaces. The Germans would dig theirs into the wall of the trench towards the enemy in order to reduce the chances of an Allied artillery shell dropping right in amongst the troops. By the war’s end, both sides were using concrete and the prefabricated metal pieces of Nissan huts to reinforce such underground spaces.

(Royal Irish Rifles ration party in the trenches at the Somme, 1916)

In the often-wet climate of the Low Countries, the trenches often need wooden reinforcements for their walls, especially where there needed to be room for two soldiers to pass each other in the trench. They also used wooden walkways to keep the soldiers’ feet out of the mud and water. Whenever possible they would also dig a channel below the walkways to drain water away from the trenches. Where the dirt would support it, they would dig out a firing step on the side towards the enemy so that soldiers could step up and fire at the enemy or step down into the relative safety of the trench. Soldiers also learned to dig a ‘grenade sump’ at or below the trench floor so that when an enemy grenade was thrown into the trench it could be kicked into the sump where the explosion would be mostly absorbed by the dirt or directed harmlessly upwards. This makes me wonder if the dugouts in the war in Ukraine have seen sumps or traps added to their entryways that would catch and contain drone-delivered grenades and bombs.

During World War Two’s war of movement, foxholes and fighting holes, and sometime slit trenches, replaced the first war’s extended trench lines (in most circumstances). This war didn’t want its troops tied down to one place long enough to build such complex systems, nor tied down manning them once constructed. While smaller and simpler, often for one or two men, and able to be defended in all directions, foxholes could still include a grenade sump and even niches dug into its sides in which to place ammunition or other supplies. Slit trenches became fighting positions for perhaps a party of two to four men. They were not intended for any long-term use because there was no real room in which to move around or keep much equipment or stores. By the Second World War they were most often seen as short-term air raid shelters or sometimes as protection against tanks which would easily drive right over the slit trench without collapsing it (soil conditions being right).

The re-emergence since World War Two of fixed defensive positions protecting key terrain points, infrastructure, populated areas, and military installations has seen the appearance again of trenches and linked bunkers along side fighting holes now encircled by razor wire vice barbed wire. And to my great amusement, it has also seen the reappearance of something that would warm Vauban’s very heart – gabions. Gabions were basically large baskets made by weaving small branches together and then filled with dirt. These were a critical tool in the processes he laid out for besieging or defending a castle. Today, we have something called a HESCO container – essentially a 21st Century gabion for putting dirt in.

Modern HESCO container gabions

Thank god for HESCO

Robert, another excellent read. You are speaking my language here. I am a lifelong student of history but specifically military history. Among many of my favorite topics is fortifications, fortresses, sieges, camps, defensive positions and so forth. One of my top 5 subjects, for only WW2, was the Maginot Line. I have always been fascinated by how utterly out of date and strategically failed that system was, the detail taken to design, the astronomically high cost to build it and ultimately how quickly France surrendered their country. Due to your background, I'm sure you have seen this, or seen better. but this link is one of the better articles I've ever found. Detailed diagrams and floor plans of placements, large maps, and great general information. Here it is if you wish to take a look. Thanks, Jim https://warfarehistorynetwork.com/article/the-french-maginot-line-its-full-history-and-legacy-after-wwii/